Sometimes it is surprising how some things are forgotten or replaced despite of once peaked attention. An example would be Valentino. Valentino now known for its trended Rockstuds had red dress long before the trend. (If you like, I would post a whole new post about it) Armani, in my opinion, would be one of the brands. Now having gained more popularity due to its beauty, it became rarer to talk about one of the core products that not only put Armani where they are globally but also represents the designer and his philosophy that made the brand, suits and sophisticated minimalism.

Biography— EARLY LIFE

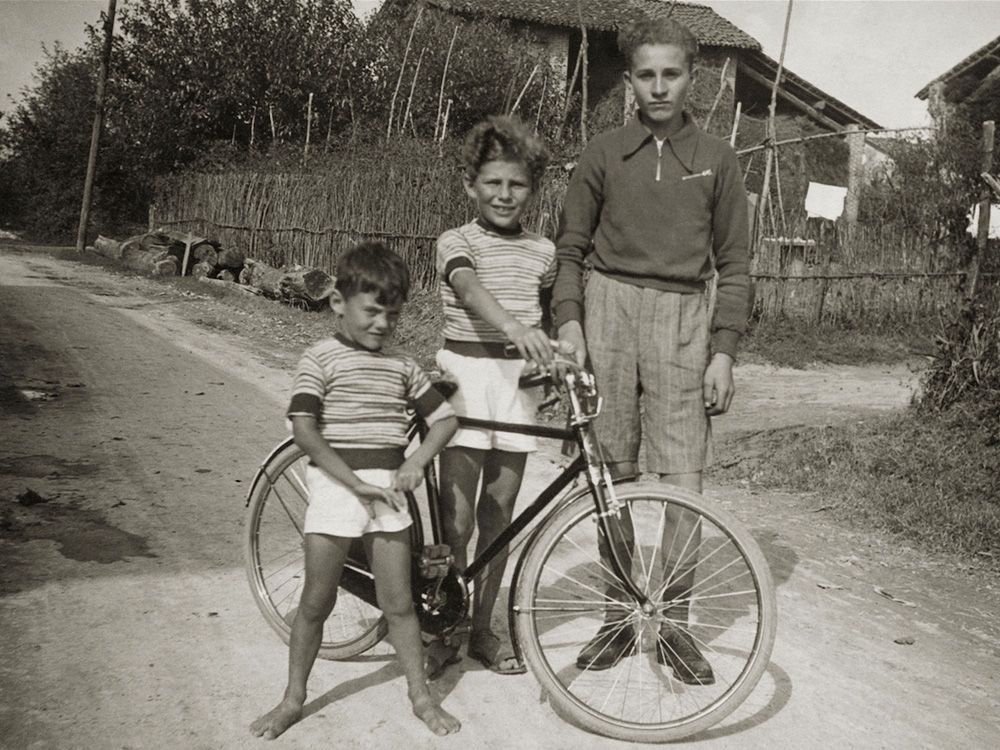

COURTESY OF GIORGIO ARMANI S.P.A

Giorgio Armani was born on July 11, 1934 in small city of Piacenza, Italy, about an hour’s drive from Milan.1 It is worth highlighting his birthplace, because whether consciously or not, the environment in which a person grows up inevitably leaves its mark— especially on creative work.

COURTESY OF GIORGIO ARMANI S.P.A

A noticeable example of the phenomenon is Domenico Dolce, whom we recently discussed. His designs consistently draw from his Sicilian heritage, through colors, motifs, and imagery rooted in the Mediterranean island— a place of sunny skies, beautiful beaches, and a layered history. (If you would like to know more, see the previous post, even if the exhibition itself does not immediately interest you.

By contrast, Piacenza— where Giorgio Armani grew up, is known for its frequent fog. Situated in the Po Valley, hemmed by Alps and Apennines, the area often traps cold, humid air during the winter months. It is therefore not surprising that Armani’s palette would later lean toward more muted tones than those of many of his Italian contemporaries. In fact, at the very inception of his brand in 1975, Armani introduced ‘greige’—a soft neutral between gray and beige — that still remains popular to this day. In an interview with Corriere di Bologna, he recalled how the concept emerged from misty morning walks in Piacenza, when the fog blended with the beige sand along the Trebbia River, producing what he termed “greige”.2 This was never merely a color. As one editor at Vogue Italia wrote:

In his visual manifesto, Giorgio Armani has made greige a way of being: not just a color choice, but a declaration of style and values. And while trends flow rapidly, his greige remains there, like a caress of light on the fabric, like a certainty that never goes out of fashion.3

Yet, at the time no one yet envisioned Armani to become a designer.

COURTESY OF GIORGIO ARMANI S.P.A

While the mists clouded the landscape, Armani’s childhood was darkened by the World War II. Scarcity and poverty were daily realities, and Armani later recalled how he quickly realized that the life was not always glamorous.4 Indeed, it is no surprise that Armani did not start working in fashion right away. He was studying medicine as suggested by his father. However after three years at the university, he was uncertain whether he wanted to continue. Military service seemed like a good temporary escape giving him time to reflect on what he truly wanted to do with his life. He served for the following two years.5

COURTESY OF GIORGIO ARMANI S.P.A

Afterwards, Armani secured a job as a window dresser in the famous Italian Department Store La Rinascente where he remained for 8 years. Eventually he came to know Nino Cerutti, an Italian businessman who owned a textile manufacture plant. At the time, Cerutti was planning to start a menswear label, which Armani quickly joined— finally beginning his career as a fashion designer.6

COURTESY OF GIORGIO ARMANI S.P.A

In the late 1960s, Armani met Sergio Galeotti, who became both his partner in life and in business. Galeotti convinced Armani to sell his Volkswagen and take the leap into independence. On July 24, 1975, Giorgio Armani S.P.A. was officially founded.7

Building an empire: History of the brand

Once he made the decision to launch his own label, he wasted no time. He debuted ready-to-wear collections for both men and women, and the business quickly gained momentum. By 1978, he had signed a manufacturing and distribution license with Gruppo Finanzario Tessile (GFT), the world’s largest manufacturer of designer clothing at the time. This ensured that Armani’s luxury ready-to-wear could be produced on a large scale while remaining under the close supervision of the designer from the company.

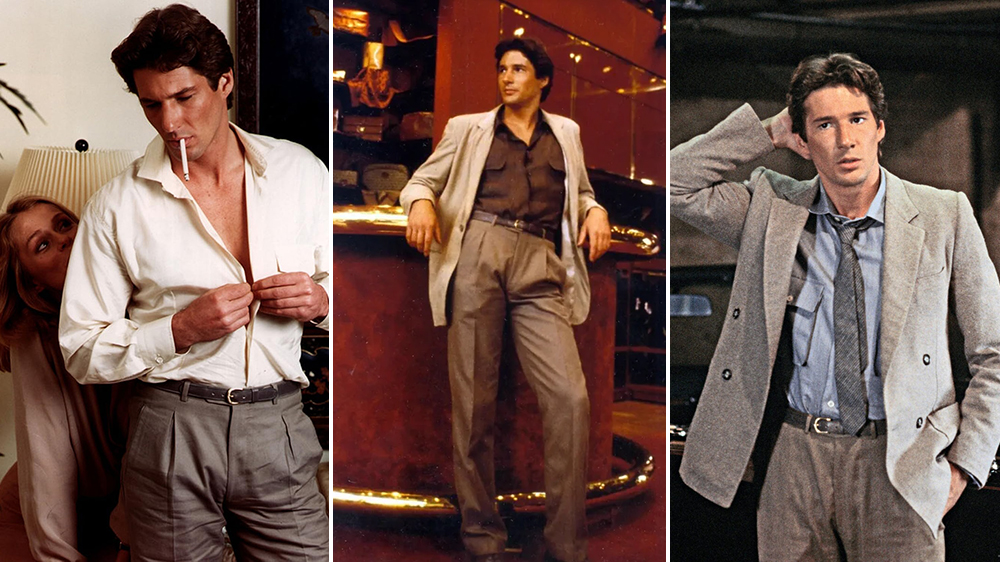

With production secured, Armani turned outward. That same year, his designs began appearing in Hollywood, culminating in the breakthrough moment of 1980 when Richard Gere wore Armani suits in Paul Schrader’s film American Gigolo. On screen, On screen, not only was the Armani label showcased through a meticulously curated wardrobe, but also Gere embodied a new style of masculinity in Armani’s soft, neutral, and relaxed tailoring— drawing contrast from the rigid, boxy and dark suits of the time. The effect was immediate; Armanis name became synonymous with effortless chic, and his brand vaulted onto the global stage.8

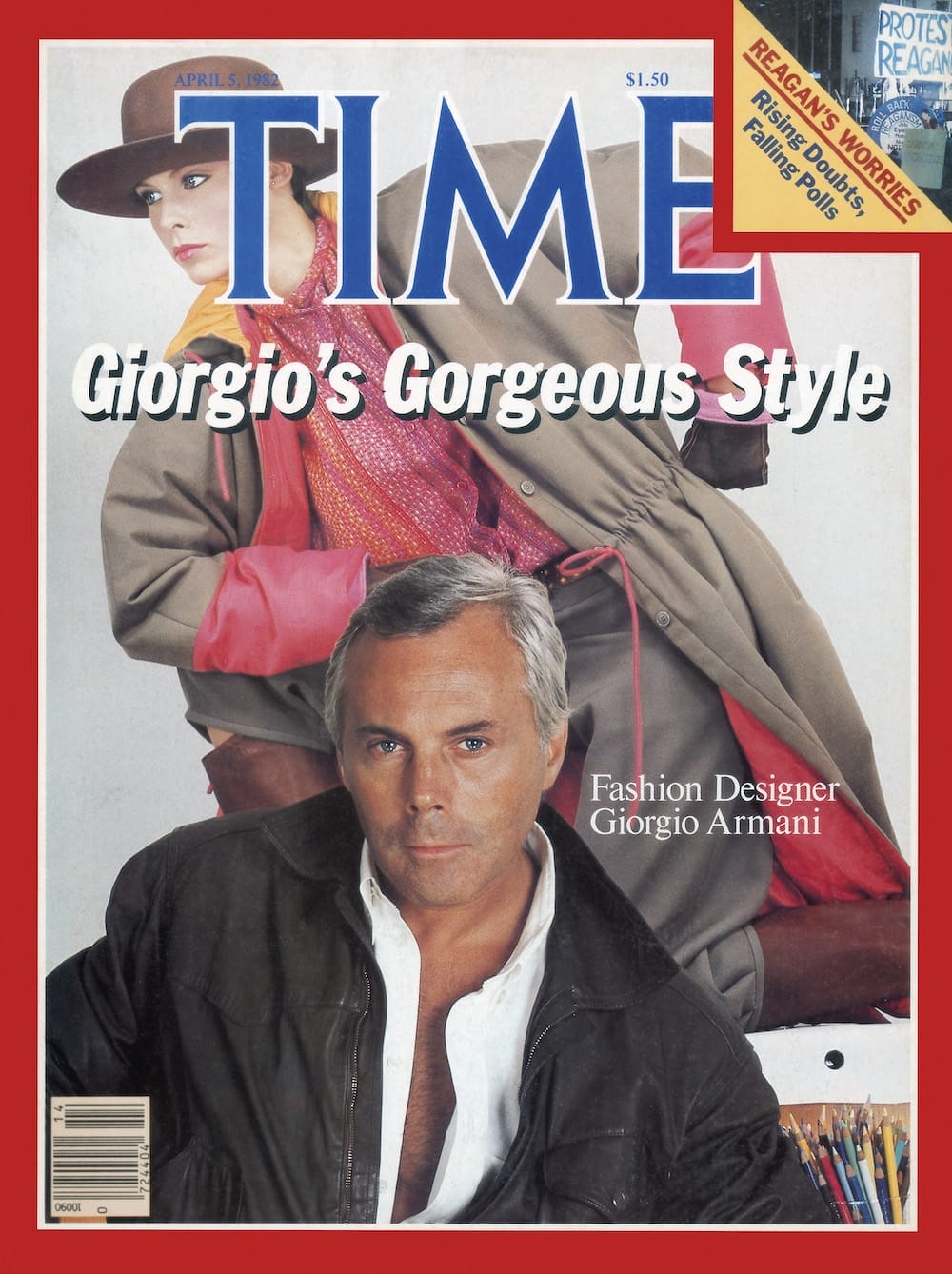

Riding this momentum, Armani expanded rapidly. In 1981 he introduced Emporio Armani, a secondary brand alongside with Armani Jeans, a casual line aimed at a younger audience.9 The following year brought further diversification with his first fragrance and Armani Junior, a line for children.10 He also became the first designer since Christian Dior to appear on the cover of Times magazine, a recognition of his growing cultural influence.11 In 1983, Armani opened his first Giorgio Armani boutique in Milan. While the business seems to go smooth, his personal life was shadowed by difficulty: his partner Sergio Galeotti was gravely ill. Armani managed much of the business jumping between Galeotti’s hospital room and office. In 1985, Galeotti died of a heart attack, a loss Armani later described with disarming candor:

When Sergio died, a part of me died too. I must say I commend myself a little because I endured an immense pain. A year spent moving from one hospital to another, I continued to work to avoid hurting him, bringing him photos of the fashion shows; in the last days, I could see the tears in his eyes. It was an extremely difficult moment that I had to overcome even against public opinion. I heard people saying: Armani is no longer himself, he will be overwhelmed by the pain, he won’t make it on his own… For this reason, when asked to participate in Giorgio Armani, I would reply: no, thank you, I can manage on my own.12

Armani proved them wrong. By 1986, just a decade after launching his brand, he was decorated by an Italian government as Grand Officer of the Order of Merit. 13 New product lines followed: eyewear in 1988, and in 1991, an American-focused A/X Armani Exchange targeting specifically younger consumers base with its first store in Soho, New York.14 Up to this point, Armani also had a licensing deals with several manufacturers and producers. However, as. It was becoming difficult to control the quality and distribution, Armani began to cancel licenses and began to reassert control over his empire. 15

The turn of the millennium marked a new apex. In 2000, Armani opened the mega concept store Armani/Manzoni 31 in Milan, bringing together his fashion, home, and lifestyle lines in one flagship space. That same year, he launched Armani/Casa, a furniture line and Armani/Fiori, a floral design venture and last but not least Armani cosmetics that is doing incredibly well today.16 To crown the mileston, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York presented the retrospective exhibition commemorating 25 years of the brand. This exhibition was a sensation, traveling from Bilbao, Berlin, London, Rome, Shanghai, Tokyo to Milan. To this day, Giorgio Armani remains the first and the last fashion designer to be given a solo exhibition at the Guggenheim.17

Armani’s expansion never slowed. In 2003, Armani started his venture in nightlife; in 2004, he launched the sportswear; in 2005, he created Giorgio Armani Prive, the haute couture line and debuted in Paris.18 Recognition followed in 2008; Armani was awarded the Legion of Honour from the French government.19 In 2015 on the 40th anniversary of his career, he inaugurated Armani/Silos in Milan, a permanent exhibition space dedicated not only to his own work but to photography and contemporary art. In 2017, Armani Group streamlined its portfolio, focusing strategically on three main brands: Giorgio Armani, Emporio Armani and A/X Armani Exchange.20 In 2021, Armani was honored as the Knight of the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit by the President of the Italian Republic. On September 4, 2025, Armani passed away at the age of 91, bringing to a close the extraordinary adventure of a man who built not just a brand but an empire.

The ARMANI SUIT

At present, Armani may be most commercially recognized for his evening gowns and expanding cosmetics line— undeniably amazing products that carry the brand’s signature elegance. Yet, to understand the core creation that propelled Armani onto the international stage, one must return to the suit, especially the jacket. It was here that Armani first articulated his design philosophy, reshaping not only fashion but also the cultural image of modern elegance. Even Armani himself said “All my work has developed around the jacket. It was the starting point for all the rest”.21 So, what is Armani suit and what makes it special?

COURTESY BILL CUNNINGHAM & YSL

COURTESY BILL CUNNINGHAM & YSL

To answer the question, one must return to Italy in the 1970s when Armani founded his brand. It was a period of profound political and cultural upheaval: as the Years of Lead (Anni di Piombo) brought vioelnt clashes between the far-left and neo-fascists organizations.22 Then, there was a rise of youth movements where students were out in the streets demonstrating against the traditional norm.23 In fashion too, change was underway. The industrial revolution was reshaping the production of clothing, and 1975– the same year Armani established his label—marked the beginning of the prêt-à-porter (ready-to-wear in French, distinguishing itself as a mass fashion in contrast to haute couture (high fashion in French).24 An Italian art critic Germano Celant explains,

The former (haute couture)’s role as an absolute, elitist vision, with its useless forms representing a theatricality of prestige and power charged with old, mummified codes linked to social and economic subjection, came to an end, and a new realm opened up, one bound to an egalitarian mentality seeking to annul differences and disadvantages, to undermine roles and disparities in dress and self-presentation.25

Since Paris was still the capital of high fashion, Milan seized the moment to establish itself as the capital of “high style ready-to-wear”.26 It was within this environment that Armani started his own creative venture, after working as a menswear designer under Cerruti. At the time, suits were still defined by formality: heavy, structured, boxy, rigid and darker colored. (One can look at photo of Yves Saint Laurent above and the jacket he is wearing) Such attire was at odds with a society moving towards the egalitarian ideals that prioritized freedom of self-expression. Armani recalled

… clothing had very little detail and made all the men look the same.I wanted clothing that could bring out a man’s personality and compliment his body. Therefore, when I started on my own,I decided to get rid of all those “structures” in jackets. This was what was making everyone look identical. I experimented with letting the clothing fall over a man’s body, bringing attention to this so-called “defect.” The idea was to deconstruct the suit, providing more freedom and movement.I thought this was essential, allowing men a more personal and real look. 27

Armani believed that the modern clothing should act as a language— an expression of the individual who moves between anthropological and social identities.28 29 Indeed, by deconstructing the jacket, Armani intertwined and blurred the boundaries of what a jacket could be: masculine yet feminine, bourgeois yet proletarian, classical yet innovative, past yet present, haute couture yet prêt-à-porter, unique yet mass-produced, structured yet free, and yet incorporeal yet corporeal. 30

I had my clothes tailor-made. It seemed indispensable to have them made to order, not out of snobbery, but because those mass-produced fashions made me feel old, shapeless, without glamour, andI wondered why they had to be so heavy, so awkward, like prisons that completely hid the body. At that time, fabric and lining were joined together with glue, which made the form rigid.I began to take everything away, padding, interfacing, linings, to look for fabrics that were classic in appearance but light, like those used in women’s fashions. As far as possible, bearing in mind production costs,I wanted to apply the secrets of couture to ready-to-wear fashion. To emphasize the shoulders in jackets, but then let the rest undulate, adapt to the body, freed from all constraints. For the first time a creased, deconstructed garment became elegant.31

Color, too, was central to Armani’s vision. He defined himself as

… the stylist without colour, the inventor of greige, a cross between grey and beige.I love these neutral tones, they are calm, serene, they provide a background upon which anyone can express himself. It isa way to connect and combine the other colours. It is a base upon which to work, and it is never definitive, never dissonant, never a passing trend, it is always something that remains, a versatile basis over which, from time to time, to imagine other things.32

This muted palette emphasized the wearer rather than the garment, ensuring that individuality, not clothing, remained at the forefront. While Armani often acknowledged the influence of artists such as Picasso, Matisse, and Kandinsky, the one he held closest to heart was Giorgio Morandi. Morandi’s still lifes demonstrated that subtle variations in tone and form were enough to create profound difference, a lesson Armani translated into fashion through his restrained use of color and detail. 33

Perhaps, it is not surprising that Armani’s looks were quickly noticed by American buyers in Florence.34 His clothing aligned seamlessly with American preferences for casual, utilitarian, and practical values in America, while also reflecting and celebrating the nation’s heterogeneity, diversity, and pluralism.35 36 The true breakthrough came with Paul Schrader’s 1980 film American Gigolo, in which Richard Gere wore Armani’s grayscale suits paired with light-colored shirts and ties. This look radiated a new urban elegance and helped propel Armani from a promising Italian designer to an international brand.37

By 1981, just a year after the film’s release, his company — launched with $10,000— was making $135 million in sales, more than double from the previous year.38 Armani’s jackets were being replicated by other European and American designer, soon becoming the industry standard.39 The press crowned Armani as a king saying “In Italy they have the Pope and Armani”.40 The success did not remain confined to menswear as the same philosophy and styles were applied to womenswear.

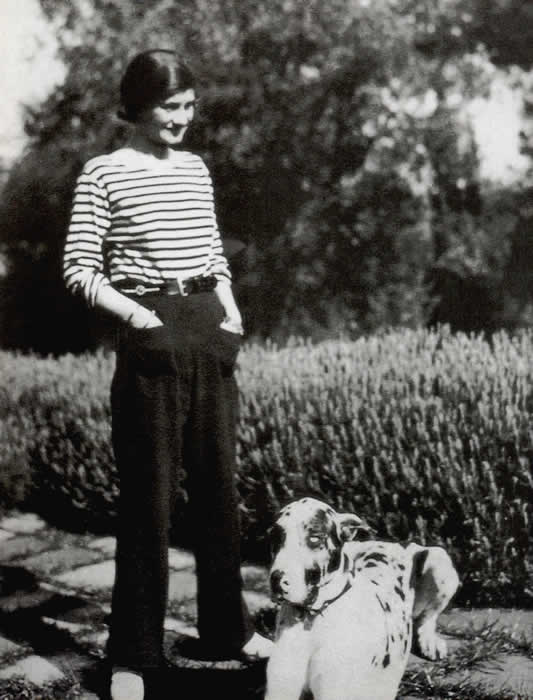

This was not too an entirely surprising move, since the whole concept of deconstructing the jacket had been inspired by French designer Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel.41 While Armani introduced elements of femininity into menswear, Chanel had done the reverse decades earlier; she sought to liberate women by modeling their clothing on menswear of her time. By stripping away excessive decors and constrictive structures of women’s clothing, Chanel offered women comfort, utility, and freedom.42 As the society in the 1980s moved further towards egalitarian ideals and traditional gender role weakened, it made sense for Armani to apply the same concepts and philosophies to womenswear. He recalled that this created “a new sexy feeling of freedom”. 43 Franca Sozzani, the former editor in chief of Vogue Italia and founder of revolutionary concept store 10 Corso Como, characterized Armani’s vision in four adjectives: “androgynous, minimal, ethnic and evening wear derived from the form of tuxedo”.44 Armani’s jackets for women were not the stiff “power suits” that had already appeared on the market, designed to mimic men’s authority. Instead, they mirrored the same qualities as his menswear: clothing that accentuated the individual and celebrated femininity while instilling confidence. His women’s jackets often featured widened lapels, rounded shoulders, and plunging necklines revealed the bosom, paired not with heels but with men’s shoes.45 Similarly, Armani used elements of tuxedo in his eveningwear, experimenting with fabrics and details such as cufflinks. Yet he always highlighted the woman’s bodies, making the look sophisticated, elegant and reserved.

Regardless of how innovative his creations were, Armani’s work consistently retained an aura of elegance, sophistication, and timelessness. He resisted the volatility. He was the creator of the trend, but never the follower of the trend. He stated in the interview

Fashion is made up of excesses, peaks, exaggeration, fanaticism. I’m against fanaticism. In the end, I think the most difficult thing to do is the simplest thing… People must not be the victims of input given by a group of people who decide what fashion is and what it isn’t. It should be remembered that certain principles of elegance that were accepted thirty years ago are now obsolete. The mentality today is different…There is a strong need to innovate and personalize like never before. This sometimes means that you don’t follow the trends for a season with the possibility of being ignored by certain fashion magazines. But it’s necessary if you want to break away from cliches.46

This consistency ultimately created the Armani style. Yet, consistency should not be mistaken for inertia, since Armani continued to produce new ideas. For example, in the late 1980s he reinvented the oversized sack suit.47 In one of the final interviews, he reflected

For people who love fashion, innovation, excess and fancy covers, this is probably true (that he stayed consistent which may seem static), but that’s a choice that I made. As long as my stores continue to sell and there is still demand from customers, and nobody can copy my products then it means I made the right choice and my brand will continue to be talked about. I wish I could show you around my Silos, so you would see how many things I did that no one has ever noticed or considered as a creative act… I have made so many different things, but what I have created is then filtered by the press which always wants the same things from Armani, customers who don’t want Armani to change or follow trends but to stay the same. Yet, Silos is the answer to anyone claiming that I have done nothing or that I repeat myself.48

Armani always had a clear sense of what defined his work and the values that unified it: “quality, innovation, comfort, creations that are logical and not irrational”. 49 From the jacket outward, this philosophy became the essence of the Armani style— an aesthetic that not only shaped a career but also sustained an empire.

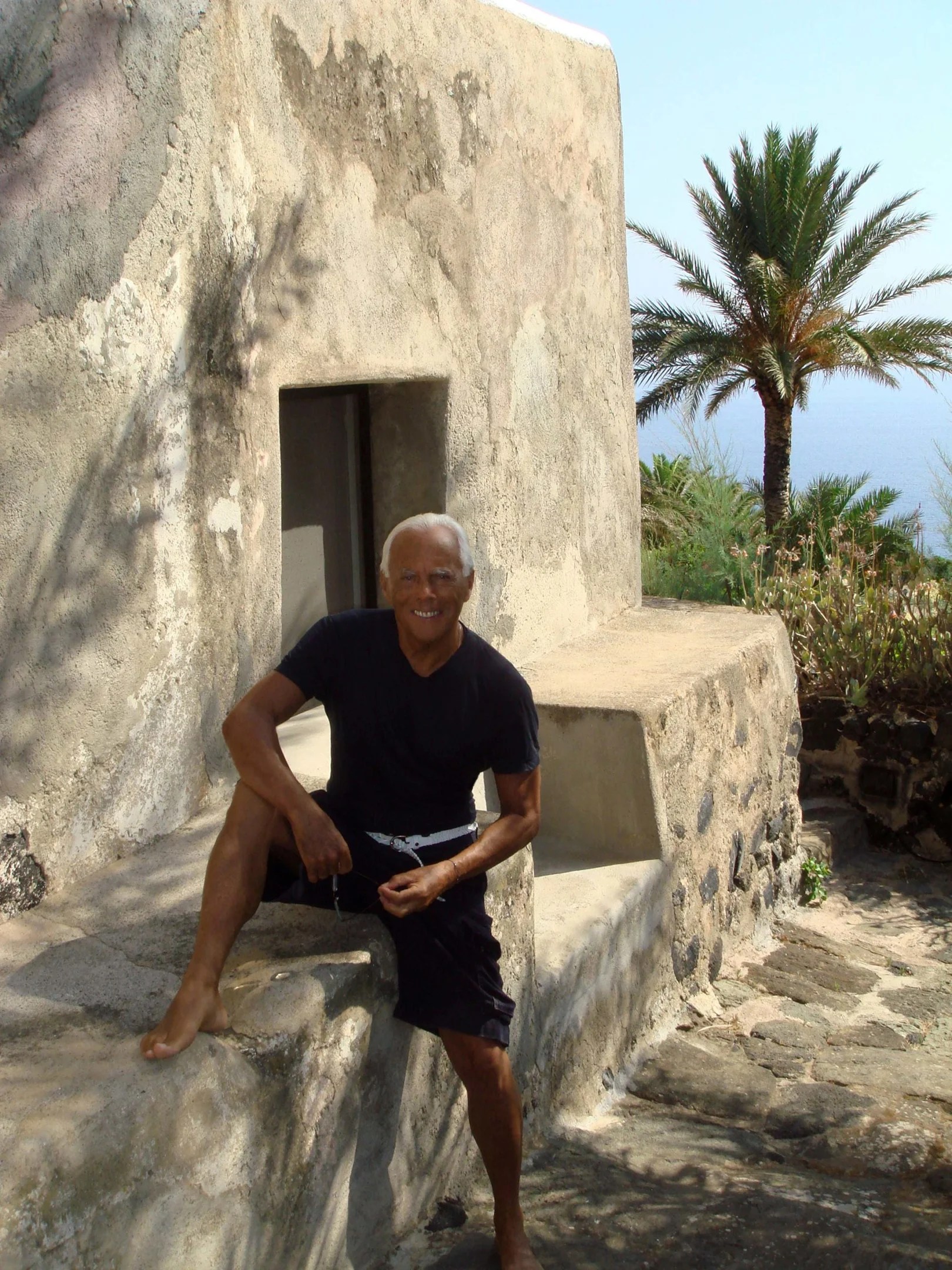

From Pantelleria, Milan, To the Armani Code — His Last Collection to Lasting Legacy

COURTESY GIORGIO ARMANI S.P.A.

While the previous section centered on the jacket—the garment that marked the foundation of Armani’s success—it is important to recognize that his design philosophy extended far beyond tailoring. On September 28, 2025, the world witnessed what would become the last collection Armani oversaw in his lifetime. Titled Pantelleria, Milan, the show carried the air of a retrospective, as if Armani himself had been composing his own epilogue. Milan symbolized the city where his career took flight and where he reshaped global fashion; Pantelleria, the volcanic island in the Mediterranean, represented his later years of retreat and contemplation. The collection began with the neutral tones that defined his style—beige, greige, and gray—presented on both male and female models walking side by side, a subtle affirmation of his vision of fluid, unforced elegance. Gradually, the garments unfolded into shades of blue, sequined with light, capturing the shimmer of Pantelleria’s sea and the iridescent calm of its horizon. What emerged was less a fashion show than a meditation: a visual autobiography that distilled the essential elements of Armani’s world.50

COURTESY GIORGIO ARMANI S.P.A

The casting highlighted not only Armani’s career but also the continuity of his vision. Models who had frequented his runways across decades returned, affirming the loyalty and intimacy that defined his presentations. Yet the most poignant moment came at the end, when Agnese Zogla, Armani’s longtime muse, stepped out alone after the others had departed. Dressed in a gown of sparkling deep blue-green with face of Armani embedded on top, she circled the Brera courtyard like Nyx, the goddess of night, as though she were bringing dusk to Armani’s long creative journey. It was an image that transcended fashion: a living allegory of closure, both mythic and deeply personal.51

The staging amplified this sense of reflection. At the piano, Ludovico Einaudi performed Nuvole Bianche, a piece inspired by watching clouds drift in the sky, serene yet charged with quiet intensity. The music carried the show from Armani’s signature neutrals—beige, greige, gray—into the luminous spectrum of blues and sea-greens that recalled the waters of Pantelleria, the island where Armani spent much of his later life. What unfolded was less a seasonal collection than a meditation: a visual autobiography that charted Armani’s path from disciplined restraint to contemplative serenity.52

COURTESY GIORGIO ARMANI S.P.A

Here, one could glimpse what might be called the Armani Code. This was never a static formula, nor a marketing slogan, nor merely the name of a perfume, but a philosophy lived out over decades. He innovated by subtraction, stripping away what was excessive to reveal clarity of form. The structures of tailoring were softened, muted palettes foregrounded the individual, and clothing was designed to empower rather than constrain. His jackets blurred boundaries between masculine and feminine, between couture and ready-to-wear, between permanence and change. Critics often remarked on his restraint, but restraint for Armani was not limitation; it was freedom. Subtle variation became the highest form of creativity, much like the still lifes of Giorgio Morandi, whom he admired.53 In an industry addicted to spectacle and volatility, he demonstrated that the truest innovation lay in fidelity to principle. The “Armani Code,” distilled from these choices, was elegance without excess, individuality without noise, memory over trend.54

PHOTO BY ISIDORE MONTAG / Gorunway.com

For now, the future of Armani feels uncertain. His will has already set in motion plans for the company to eventually change hands, whether through a sale to a major group or a market listing.55 What this means for the brand is still unknown. Yet whatever direction the business takes, the essence of Armani is not something that can be transferred or diluted. His principles are already etched into the way we think about dressing: clothes that highlight the person, not the garment; elegance that lasts, not spectacle that fades. Armani once wrote, “Elegance is not about being noticed, it’s about being remembered”.56 Today those words read like his epitaph, a reminder that while the business may change, the Armani Code endures as a lasting definition of modern elegance.

Bibliography

- Gross, Rachel Elspeth. 2025. “Remembering Giorgio Armani (1934–2025).” Forbes, September 4, 2025. https://www.forbes.com/sites/rachelelspethgross/2025/09/04/remembering-giorgio-armani-1934-2025/ ↩︎

- Melchioni, Vittoria, and Stefano Pancini. 2025. “Piacenza piange Giorgio Armani: l’infanzia e i tortelli della madre, il ‘greige’ dalla sabbia del Trebbia, le donazioni agli ospedali.” Corriere di Bologna, September 4, 2025. https://corrieredibologna.corriere.it/notizie/cronaca/25_settembre_04/piacenza-piange-giorgio-armani-l-infanzia-e-i-tortelli-della-madre-il-greige-dalla-sabbia-del-trebbia-le-donazioni-agli-ospedali-dae8456f-d2cb-4f47-ba43-7d01ca686xlk.shtml.

↩︎ - Oliva, Selene. 2025. “Greige di Giorgio Armani, il colore neutro intramontabile segno dell’eleganza armaniana.” Vogue Italia, September 5, 2025. https://www.vogue.it/gallery/giorgio-armani-greige-colore-moda-elegante-intramontabile-look-foto.

↩︎ - Gross, Rachel Elspeth. 2025. “Remembering Giorgio Armani (1934–2025).”

↩︎ - Filippini, Roberta. 2025. “La vita di Armani: la bomba a farfalla scoppiata vicino, il lavoro alla Rinascente e la svolta con Cerruti. Come è diventato Re Giorgio.” Il Riformista, September 4, 2025. https://www.ilriformista.it/la-vita-di-armani-la-bomba-a-farfalla-scoppiata-vicino-il-lavoro-alla-rinascente-e-la-svolta-con-cerruti-come-e-diventato-re-giorgio-480101/.

Filippini, Roberta. 2025. “La vita di Armani: la bomba a farfalla scoppiata vicino, il lavoro alla Rinascente e la svolta con Cerruti. Come è diventato Re Giorgio.” Il Riformista, September 4, 2025. https://www.ilriformista.it/la-vita-di-armani-la-bomba-a-farfalla-scoppiata-vicino-il-lavoro-alla-rinascente-e-la-svolta-con-cerruti-come-e-diventato-re-giorgio-480101/.

↩︎ - Ibid. ↩︎

- Armani. 2025. “Our History.” Armani Values. Accessed September 6, 2025. https://armanivalues.com/overview/our-history/.

↩︎ - Kelly, Juno. 2025. “How American Gigolo Made Armani a Household Name.” Culted, September 5, 2025. https://culted.com/how-american-gigolo-made-armani-a-household-name/.

↩︎ - Armani. 2025. “Our History.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. 2000. “Giorgio Armani: A Retrospective — History.” Guggenheim Museum. http://pastexhibitions.guggenheim.org/armani/history.html. ↩︎

- Cazzullo, Aldo, and Paola Pollo. 2025. “Intervista ad Armani: ‘Non volevo fare il sarto, ma ora ho paura di lasciare un vuoto.’” Corriere della Sera, September 4, 2025. https://www.corriere.it/cronache/25_settembre_04/intervista-armani-937e12da-47a1-4d52-a076-69a1158c9xlk.shtml.

↩︎ - Armani. 2025. “Our History.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Socha, Miles. 2025. “Giorgio Armani, 1934–2025.” Women’s Wear Daily (WWD), September 4, 2025. https://wwd.com/fashion-news/fashion-features/article-1183244/.

↩︎ - Armani. 2025. “Our History.” ↩︎

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. 2000. “Giorgio Armani.” Guggenheim Museum. https://www.guggenheim.org/exhibition/giorgio-armani-2.

↩︎ - Armani. 2025. “Our History.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Celant, Germano “Preface: Giorgio Armani: Toward the Mass Dandy,” in Giorgio Armani, ed. Germano Celant and Harold Koda, with Susan Cross and Karole Vail (New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2000), xix.

↩︎ - Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey. 2020. Italian Neofascism and the Years of Lead: A Closer Look. Monterey, CA: Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism (CTEC). https://www.middlebury.edu/institute/academics/centers-initiatives/ctec/ctec-publications/italian-neofascism-and-years-lead-closer-look

Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey. 2020. Italian Neofascism and the Years of Lead: A Closer Look. Monterey, CA: Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism (CTEC). https://www.middlebury.edu/institute/academics/centers-initiatives/ctec/ctec-publications/italian-neofascism-and-years-lead-closer-look ↩︎ - Aspesi, Natalia. “Milan in the 1970s and 1980s.” In Giorgio Armani, edited by Germano Celant and Harold Koda, with Susan Cross and Karole Vail, 20–21. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2000.

↩︎ - Celant, Germano “Preface: Giorgio Armani: Toward the Mass Dandy” xvi ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Aspesi, Natalia. “Milan in the 1970s and 1980s.” ↩︎

- Sischy, Ingrid. “Interview with Armani.” In Giorgio Armani, edited by Germano Celant and Harold Koda, with Susan Cross and Karole Vail, 12. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2000.

↩︎ - Blonsky, Marshall. “The Armani Army.” With the collaboration of Edmundo Desnoes. In Giorgio Armani, edited by Germano Celant and Harold Koda, with Susan Cross and Karole Vail, 26. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2000.

↩︎ - Celant, Germano “Preface: Giorgio Armani: Toward the Mass Dandy” xviii ↩︎

- Ibid. xviii-xix ↩︎

- Aspesi, Natalia. “Milan in the 1970s and 1980s.” 23 ↩︎

- Celant, Germano “Preface: Giorgio Armani: Toward the Mass Dandy” xxii-xxiii ↩︎

- Sischy, Ingrid. “Interview with Armani”. 13-15 ↩︎

- Aspesi, Natalia. “Milan in the 1970s and 1980s.” 23 ↩︎

- Morris, Bernadine. “Style around the World: An American View.” New York Times Magazine, August 25, 1985. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/08/25/magazine/style-around-the-world-an-american-view.html. ↩︎

- Yotka, Steff. “In America: A Lexicon of Fashion—the Costume Institute’s 2021 Exhibition.” Vogue, September 18, 2021. https://www.vogue.com/article/in-america-a-lexicon-of-fashion-costume-institute-exhibition. ↩︎

- Aspesi, Natalia. “Milan in the 1970s and 1980s.” 23 ↩︎

- Ibid. 23-24 ↩︎

- McCarthy, Patrick. “Menswear Revolution.” In Giorgio Armani, edited by Germano Celant and Harold Koda, with Susan Cross and Karole Vail, 86. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2000. ↩︎

- Aspesi, Natalia. “Milan in the 1970s and 1980s.” 23 ↩︎

- Sischy, Ingrid. “Interview with Armani”. 13 ↩︎

- Menkes, Suzy. “Liberty, Equality and Sobriety.” In Giorgio Armani, edited by Germano Celant and Harold Koda, with Susan Cross and Karole Vail, 69. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2000. ↩︎

- Sischy, Ingrid. “Interview with Armani”. 12 ↩︎

- Sozzani, Franca. “On Womenswear.” In Giorgio Armani, edited by Germano Celant and Harold Koda, with Susan Cross and Karole Vail, 75. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2000. ↩︎

- Ibid. 81 ↩︎

- Sischy, Ingrid. “Interview with Armani”. 14 ↩︎

- McCarthy, Patrick. “Menswear Revolution.” 86 ↩︎

- Amed, Imran. “Giorgio Armani on His Life, Legacy and Lessons for the Future of Fashion.” Interview by Imran Amed. YouTube video, 52:08. Posted by The Business of Fashion, March 11, 2021. https://youtu.be/x6zd18LUxp4?si=ghKNSeGuDQY7YUbo. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Reuters, “Giorgio Armani Unveils Late Designer’s Last Collection,” Reuters, September 28, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/lifestyle/giorgio-armani-unveils-late-designers-last-collection-2025-09-28/. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Di Selina, Oliva. “Giorgio Armani: Greige, il colore della moda elegate,” Vogue Italia, September 4, 2025, https://www.vogue.it/gallery/giorgio-armani-greige-colore-moda-elegante-intramontabile-look-foto. ↩︎

- Celant, Germano “Preface: Giorgio Armani: Toward the Mass Dandy” xviii ↩︎

- Danziger, Pam. “Giorgio Armani’s Will Opens the Door to a Partial Sale or IPO,” Forbes, September 12, 2025, https://www.forbes.com/sites/pamdanziger/2025/09/12/giorgio-armanis-will-opens-the-door-to-a-partial-sale-or-ipo/. ↩︎

- Armani, Giorgio. “Armani Disarmed,” Emporio Armani Magazine (Milan), no. 14 (September–February 1995–96). 8 ↩︎

![[Review] Dolce & Gabbana Dal Cuore Alle Mani — Yet the Best Combining History, Art and Craftsmanship](https://thecrtd.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/image-2.jpeg?w=1024)

Leave a comment